A Journey to the Peruvian Amazon: "From the Andes to the Amazon"

Admiring the evolution of the active rivers in the headwaters of the Amazon on Google Earth Engine the other day, I remembered this 1995 journey to Manu. I was particularly interested to see the eventual cut-off of the meander loop where we saw water flooding over the meander neck and trees toppling into the river on December 11th 1995 (near the macaw clay-lick).

My original photos are lost, but I'll see what I can rescue from copies (the small images). The text below is from a 1996 article in "Le Perroquet", Gabon. I have added images from Google Earth.

My original photos are lost, but I'll see what I can rescue from copies (the small images). The text below is from a 1996 article in "Le Perroquet", Gabon. I have added images from Google Earth.

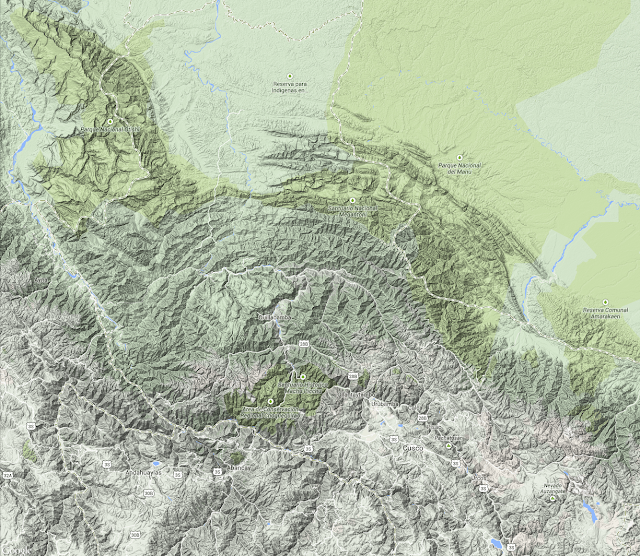

The terrain between Cusco and Manu.

From the Andes to the Amazon

In Gabon, the equatorial African forest

is within easy reach. There’s another rainforest, which, in its more pristine

areas, is even richer in animals and plants: that of the Amazon Basin. There is thought to be a greater variety of living things here than anywhere else in the world. As an

example, the Manu Biosphere Reserve of southeastern Peru protects more than

1000 species of native birds and over 200 species of mammals, including

monkeys, jaguars and giant river otters.

It sounded tempting,

so we made a journey to Manu in December 1995, travelling from Qosqo (or

Cusco), high in the Peruvian Andes across the Puna grasslands, down through the

cloud forest to the lowland rainforest of the upper Amazon.

The journey

The Inka

highlands

At 3300 m, it

takes the body a while to adjust to the altitude in the old Inka capital, now

officially known by its Quechua name of Qosqo. The city was laid out in the

form of a puma with its head represented by the hill at the north-western end

of the town. The top of the puma’s head is defined by the massive ramparts of

Sacsayhuaman, built of perfectly-fitted giant polygonal blocks of stone. The

largest of these are over 8 m tall.

Sacsayhuaman

The area

around Qosqo is fantastically rich in the remains of the Inka Empire. An

excursion to the north took us to the Urubamba (or Vilcanota, in its upper

reaches) valley. The river has a fertile floodplain where the world’s best

maize is grown. Flowing northwest, it loops around the base of the mountain on

which Machu Picchu is perched, and eventually takes a sharp turn to the right

to feed into the Amazon. Many Inka fortresses, agricultural terraces, towns and

temples lie along its course.

Near Machu Picchu, we stayed at the foot

of the mountain by some hot springs, at a little town called Aguas Calientes

(“hot waters”). In the early morning a bus took us on the zigzag track up the

hill and after a walk through the ruins of Machu Picchu we climbed up to Huayna

Picchu (“Young Peak” in Quechua) for a superb view over the ancient city. After

climbing back down the narrow trail, holding onto ropes along the many steep

sections, we went for a final wander through the deserted ruins (the tourist

train had broken down between Qosqo and Machu Picchu). Here, half way up a

stone Inka staircase, we saw our first Peruvian wild animals: a pair of

mountain vizcachas, the wild relatives of the domestic chinchilla.

Machu Picchu from Huayna Picchu

Vizcachas

on an Inkan staircase, Machu

Picchu

“Hitching

post of the sun”

The Inka Empire

was called the Empire of the Four Quarters, “Tahuantinsuyo” in Quechua. Qosqo

was the centre point. To the south was Collasuyo (northern Chile and

Argentina), to the west Contisuyo, to the north Chinchaysuyo (Equador and

Colombia), and to the east, the Amazon rainforest, or Antisuyo. The 9th Inka,

Pachakuti Inka Yupanki, is thought to have launched the main military campaigns

into Antisuyo. Later, the native tribes refused to send tribute to Pachakuti’s

son, Topa Inka Yupanki (Inka from 1471 to 1493), provoking a punitive military

campaign. Eventually the four forest indian nations, Opataris, Manaries,

Chunchos and Manosuyo, were conquered. “Manu” is thought to derive from this

last name. Jungle archers formed an important part of the Inka imperial army,

serving on military campaigns as far north as Ecuador.

Antisuyo and,

in particular, the Manu reserve was our destination for the following day.

Into the

Cloud Forest

8/12/95.

Leaving Qosqo at 5.00 in the morning we set off in a powerful vehicle, a cross

between a bus and a truck, heading towards the northeast. We two were the only

tourists. The remaining occupants were: Eliana, our knowledgeable Peruvian

guide; our cook; and a few of their friends hitching a lift to some of the more

distant settlements. From the bus we looked out over a bleak landscape of

grasslands, with deep valleys, abandoned villages, with occasional birds

(mountain caracaras, flocks of siskins, hawks and a giant hummingbird).

Near the ancient Inka city of Paucartambo we passed a line of pre-Inka

burial towers, called “chullpas” along a ridge bounded by cloud-filled valleys.

The other place to see these is near the shores of Lake Titicaca. Here we were

at about 4000 m above sea-level. Frequent cups of coca leaf tea from a thermos

helped against the cold and altitude.

In the

afternoon we reached a place called Tres Cruces where we had a vast view across

the high elevation grasslands, beneath them scattered patches of elfin forests

in sharp valleys and beyond them the cloud-covered Amazon Basin. In Inka times

this place was used to observe the summer and winter solstices. From here we

were to descend 3500 m over the next two days to the lowland forests of the

Manu River.

View to NE from Tres Cruces towards the Rio Alto Madre de Dios, Manu and the Amazon Basin.

Our campsite that night was next to a

roaring mountain stream, surrounded by dense forest. Before dark we walked to

the display ground of a brilliant orange bird, the Andean Cock-of-the-rock.

They carry a crest of orange feathers that flops forwards, almost obscuring

their beaks. A group of males dance and squawk here at dusk and dawn, trying to

tempt the dull brown females.

Andean

Cock-of-the-rock

9/12/95:

A variety of birds put in brief appearances as we ate breakfast: turkey-like

Andean Guans, tiny Turquoise Tanagers, Oropendulas (“dangling gold” after their

yellow tails) and female Cock-of-the-rocks. This is a luxuriant green world

with huge tree ferns and begonias, bromeliads and mosses covering most

available space on tree branches. Walking through the forest here we saw, in

one field of view, a mixed flock of spectacular green and red Golden-headed

Quetzales, Blue Jays, Oropendulas, Squirrel cuckoos and Golden-green

Woodpeckers. As Eliana, our guide took photos of rare orchids to take back to a

botanist friend we noticed a family of woolly monkeys including a mother with

her child hanging on to her back, all moving gracefully through the trees.

Unlike African monkeys, these use their tails as a sinuous fifth arm.

Our

campsite in the cloud forest

Orchid

10/12/95: 4.00 am departure from our campsite as

we continued down the frightening road. Many crosses by the roadside marked

spots where trucks had gone over the edge.

Near the town

of Pilcopata we had a forced stop where a truck on its way to Qosqo had lost

one wheel over the edge of the road next to a drop into the valley below, but

had just managed to stay on the road. Next to the truck, Dusky Titi monkeys sat

watching us from high in a tree, vultures circled on thermals above; hummingbirds, parrots, macaws, jays and hawks hovered, perched or flew past.

After an hour a tractor came up from the town and managed to push the truck

sideways, fully on to the road. The journey continued.

At a place

called Atalaya, we transferred our things to a piragua on the Rio Alto Madre de Dios (known as Amarumau, “River

of the Great Serpent” in Quechua). Huge

flocks of white-collared swifts swooped back and forth across the river and

white-winged swallows perched on the points of sticks projecting from the

river.

Rio

Alto Madre de Dios

The waters of the Alto Madre de Dios are

fast-flowing and rough here. Many birds decorated the banks: pink spoonbills,

kingfishers, herons, egrets, macaws and always vultures circling above. Small

settlements of Piro indians occur along the river banks here. We continued past

the mouth of the Manu River and reached our night stop, a small rustic lodge at

a place called Blanquillo. In a visit to a nearby oxbow lake a strange deep

humming sound permeated the air. This was caused by electric eels in the lake

beneath us. Squirrel monkeys chirruped from the lakeside bamboo.

Here, in the

do-it-yourself “shower” (a bucket of muddy water from the oxbow lake), we had

our introduction to the giant mosquitoes (which were completely immune to our

repellents) ants and a variety of other Amazonian insects.

The

Lowland Rainforest

11/12/95:

As usual, an early morning start. We took the boat down river a couple of hours

until we arrived at a macaw clay-lick. This was a cliff on the outer arc of a

bend in the river. Over a few hours many (12) species of macaws, parrots and

parakeets gathered ready to eat the exposed soil. The minerals in the soil are

thought to act as a kind of jungle antacid that enables them to eat

normally-poisonous seeds. We sat in a floating hide, watching through a

telescope. Several cliff-falls startled the macaws. It was our turn to be

startled when a fully grown tree keeled over into the river.

Tree-fall

From the macaw

lick we turned round to head upstream to Manu Lodge, dodging numerous floating

logs in the water. We saw our first sideneck turtles, basking on a log. These

are rare elsewhere in Amazonas due to hunting and stealing of their eggs.

Shortly before

dark we pulled up at the river bank and walked through the forest to reach Manu

Lodge, an elegant structure built of drifted Ceiba wood next to Cocha Juarez,

an oxbow lake. Walking by oil lamp towards the showers we noticed the long line

of leaf-cutting ants and followed them to the end of their track where a tunnel

descends to their underground home.

Capped Heron

On first

impressions, apart from the lack of elephant and buffalo tracks, we could have

been in the equatorial African rainforest. The largest animal in the Amazon is

the Tapir and this doesn’t seem to make clear roads. Several of the trees

seemed very familiar: strangler figs, umbrella trees and spiky Bactris and other palms.

Bromeliad

12/12/95: At 4.30 am we were woken by an eerie

howling, sounding like a chorus of ghosts. Later we learned that all this noise

was made by a single male howler monkey. Walking the trails around the oxbow

lake we encountered a group of small nervous saddle-backed tamarins, which

unlike other monkeys have claws that let them clasp tree trunks like squirrels.

A little later a noisy group of white-fronted capuchin monkeys ran along the

spines of palm fronds, each of them stopping to stare at us for a moment before

continuing on their way. We climbed to two lookout points with fine views over

the top of the forest. Here we set up a telescope to watch a selection of

spectacularly-coloured small birds, mainly tanagers and hummingbirds. At

intervals small groups of macaws would fly past, flashing blues, reds and

yellows. Walking back down to the lake, as Eliana stopped to point out a

tarantula, several metres of previously-hidden black snake slithered away from

us on the ground.

Howler

Monkeys

We returned to

the lodge in a small dugout canoe, past black caimans lurking in the lakeside

bushes and groups of Hoatzins, a large primitive-looking bird with a crest of

spiky feathers.

Black cayman ("Clothilde")

Huatzin

13/12/95:

The day started with a morning canoe trip on Cocha Juarez. Early on we passed

the howler monkeys lazing high up a tree. When we came back they were still

there, lethargically nibbling leaves. Walking close to the lodge we saw a lone

male black spider monkey swinging at speed through the tree tops. A short while

later, more capuchin monkeys and another group of tamarins crossed our path.

In the

afternoon we were back on the river for a visit to a Blue-and-Yellow Macaw

nesting site. Here, after wading thigh-deep through a swamp, we climbed a green

scaffolding tower, put up by Frans Lanting to take photos for the 1994 National

Geographic article on macaws. In addition to the Blue-and-yellows there were

Red-bellied Macaws, jacamars, tanagers, a Slate-coloured Hawk and pairs and

threesomes of Scarlet and Red-and-green Macaws passing overhead. At the top of

the platform, changing films, I dropped the recently-exposed roll and just

caught it as it bounced towards the swamp below. I breathed again.

14/12/95:

This was the day we went looking for giant river otters in another oxbow lake,

Cocha Otorongo, further up the Manu. We spent some time watching side-neck

turtles in lines of up to eight on tree roots. Just as we began to think we

weren’t going to see any otters, a family of eight came speeding down the lake

towards us. They entertained us for an hour, catching fish and eating them head

first, stretching out on fallen tree trunks, rolling an unfortunate turtle, and

generally tumbling and enjoying themselves. This was a rare privilege since

these 2 m otters are very close to extinction, a result of intense fur poaching

up until the 1970s. Manu has the largest protected population - about 48.

Elsewhere they survive in small pockets, scattered across the Amazon.

Cocha Otorongo

Large turtle in Cocha Otorongo

Lunch at the

lodge was enlivened when Cristina looked up and noticed a large length of brown

snake above our heads in the angle of the ceiling. A moment later we saw its

head nearly 2 m further along! We watched until it found a way out on to the

roof (Cristina not very happy about this). In the late afternoon, an agouti, a

kind of giant guineapig ran across a clearing next to the lodge. At dusk a family

of spider monkeys swung through the tree tops and dangled from their tails,

ripping off young branches and leaves.

A snake in the house

15/12/95: After the usual 4.30

am wakeup howling session from the local Red Howler male, we said farewell to

Manu Lodge, walked the trail to the river and travelled by boat back down the

Manu River to a small airstrip next to a military base (established to prevent

a cocaine smuggling operation). Waiting for our tiny plane at the military base, we fed banana to an unhappy captive baby capuchin monkey. Clouds of

many-coloured butterflies hovered over the muddy river bank. We had found some

shade to relax in when we were brought back to a sudden state of alertness: a young

soldier let off a series of bursts of machine gun fire over a

passing boat which had not stopped to register.

On the short

flight back to Qosqo we crossed the ground we had travelled a week earlier,

starting with views of endless forest similar to aerial views of Gabon, then

passing the high snow-covered Andes of the Urubamba Range. Two small bright

green Tui Parakeets peeked out of the pocket of a fellow passenger.

It had been an

exciting, rewarding and tiring trip and we were looking forward to not being

woken up at 4.30 am. In a week we had seen over 120 species of bird, 13 species

of mammal (8 of them monkeys) and 7 species of reptile and enjoyed spectacular

river and forest scenery. We left Peru behind us and continued south, for a relaxing

Christmas and New Year amidst the volcanoes, lakes and more temperate forests

of Chile.

Comments

Post a Comment